Consider a random variable X obtained from a random experiment E with the mean, variance  and density function

and density function  .

.

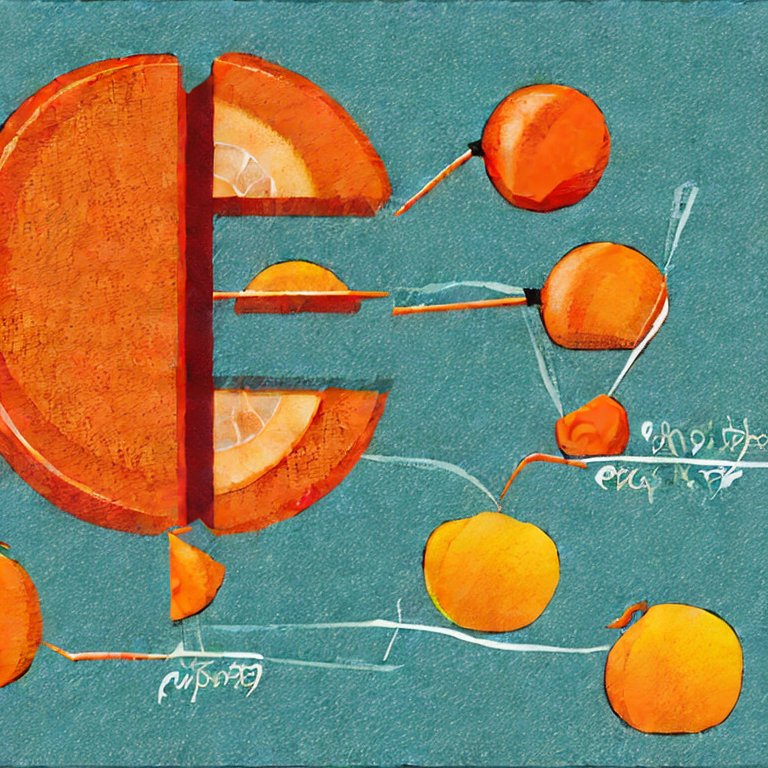

First- and Second-order approximations. The mean and variance provide a simple, partial statistical description of the random variable X that is easy to understand intuitively: the mean is the center of mass of the distribution  , while the standard deviation

, while the standard deviation  is a measure of the spread of the distribution away from the mean. The complete statistical description of X is of course provided by the density function

is a measure of the spread of the distribution away from the mean. The complete statistical description of X is of course provided by the density function  .

.

Specifying a distribution by its moments. An alternative statistical description of a random variable is in terms of its moments: ![\mu_n^n \doteq E \left[ X^n \right],~n=1,2, \dots \infty](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmu_n%5En+%5Cdoteq+E+%5Cleft%5B+X%5En+%5Cright%5D%2C%7En%3D1%2C2%2C+%5Cdots+%5Cinfty&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) . To understand the moments of a distribution intuitively, consider the characteristic function

. To understand the moments of a distribution intuitively, consider the characteristic function ![\Phi_X(\omega) \doteq E \left[ e^{j \omega X} \right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5CPhi_X%28%5Comega%29+%5Cdoteq+E+%5Cleft%5B+e%5E%7Bj+%5Comega+X%7D+%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) . Mathematically, the characteristic function is the Fourier transform of the density function

. Mathematically, the characteristic function is the Fourier transform of the density function  . For low “frequencies”

. For low “frequencies”  , we can approximate the characteristic function by a Taylor Series:

, we can approximate the characteristic function by a Taylor Series:  .

.

Roughly speaking, the lower-order moments provide a coarse, “low frequency” approximation to the distribution, and higher-order moments supply finer-grained “high-frequency” details.

The Law of Large Numbers. Consider N independent repetitions of the experiment E resulting in the iid sequence of random variables  . The sample mean random variable

. The sample mean random variable  has the mean

has the mean  and variance

and variance  .

.

Clearly, since the variance of S vanishes as  , the random variable S converges to its mean. This is also easily confirmed from

, the random variable S converges to its mean. This is also easily confirmed from  . This is one version of the famous Law of Large Numbers (LLN).

. This is one version of the famous Law of Large Numbers (LLN).

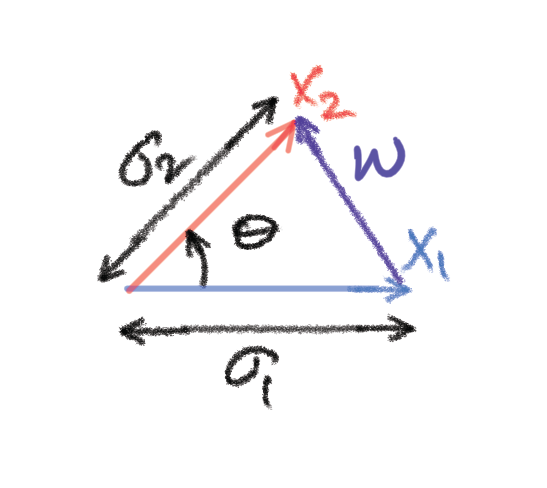

Deviations from the Mean. The LLN represents a first-order approximation to the distribution of the sample mean S. To refine this approximation and look at how S is distributed around its mean, consider the “centered random variable”  . This random variable has the characteristic function

. This random variable has the characteristic function  . This is simply the LLN all over again i.e.

. This is simply the LLN all over again i.e.  . It turns out that deviations from the mean, being second-order effects, are small and vanish asymptotically!

. It turns out that deviations from the mean, being second-order effects, are small and vanish asymptotically!

Central Limits. To prevent the deviations from the sample mean from becoming vanishingly small, we must magnify or zoom into them explicitly. Thus, we are led to define  . This random variable has zero mean and variance

. This random variable has zero mean and variance  which is finite and its characteristic function is:

which is finite and its characteristic function is:  .

.

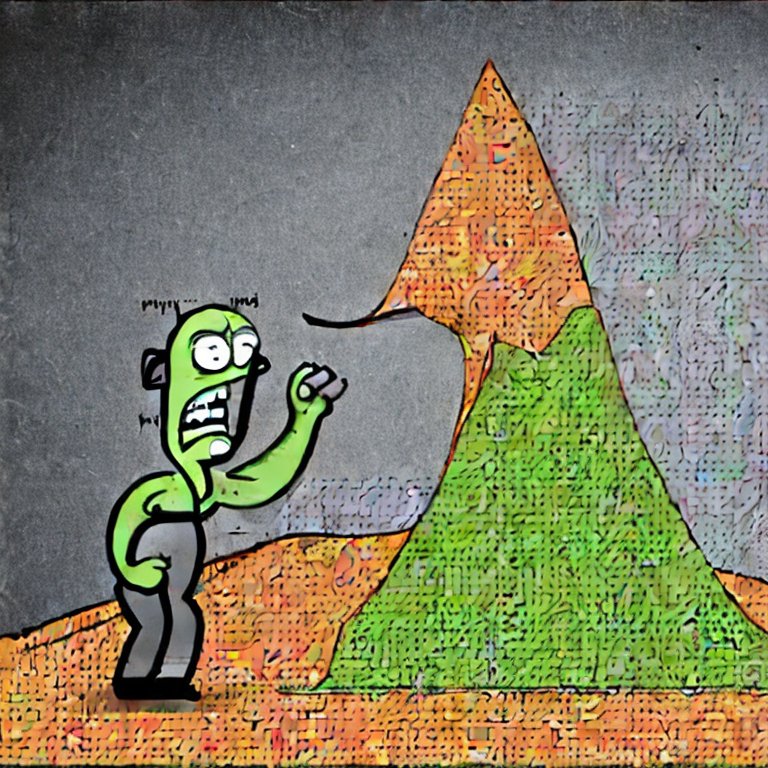

This is a version of the famous Central Limit Theorem (CLT) that says that the small deviations around the sample mean of a large number of independent random variables  follow a Gaussian distribution regardless of the actual distribution of the

follow a Gaussian distribution regardless of the actual distribution of the  ‘s!

‘s!

Random Mixing Smooths over Fine Details. In fact our simple derivation above does not require that the  ‘s be identically distributed; only that they have the same mean and variance and that they are independent.

‘s be identically distributed; only that they have the same mean and variance and that they are independent.

The CLT may help explain why the Bell Curve of the Gaussian distribution is so ubiquitous in nature: for complex, multi-causal natural phenomena, when we look at the aggregate of many small independent variables, the fine details of the underlying variables tend to get obscured.

There are many Internet resources that provide nice illustrations of the CLT. Here’s one from this website:

However, it is important to recognize that the CLT is an asymptotic result and usually applies in practice as an approximation. Following the logic of the derivation above, we should expect the CLT to only account for the coarse features of the distribution; in particular, the Gaussian approximation should not be relied on to predict the probability of rare “tail events”.

One place where the Gaussian approximation works really well is for the distribution of noise voltages in circuits. This is understandable when the noise is thermal in origin. Of course noise voltages are random waveforms, and their statistical description is more complex than that of a single random variable. In particular, we need to discuss the joint distribution of multiple Gaussian random variables or equivalently, Gaussian random vectors. This is a topic for Part 2.